2023 Iowa Child Care Workforce Study

Appendix C

Administrator Focus Groups

SUMMARY OF FINDINGS

To supplement the individual providers’ survey and center- and home- based provider focus groups, we conducted several focus groups with center administrators to obtain additional information about workforce recruitment and retention strategies. This appendix reflects the 8 in-person provider focus groups as well as 3 individual interviews conducted with directors who could not participate in the focus groups, for a total of 37 participants. Transcripts from audio recordings of the focus groups and interviews were generated, checked against recordings, and deductively coded using themes and subthemes identified from prior survey and focus group work (see Appendices A and B, for more information).

Primary themes from the administrator focus groups included:

- Higher pay is critical to recruiting and retaining enough employees to be adequately staffed, and parents cannot be the source of the additional funds. Current salary supplement programs, such as WAGE$ and recruitment and retention bonuses have the potential to help meet this need but are not doing so at this time.

- Providing benefits such as health insurance and retirement is financially challenging for programs so most do not offer these. Free or reduced-cost child care is a more frequently offered and utilized benefit.

- Administrators have been struggling to recruit staff since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, and the low wages and lack of benefits is not helping. Administrators have been hesitant to use state financial support and incentives as recruitment tools because they perceive the funding could become unavailable with little notice.

- Education is a key factor in determining pay. There are programs to assist with helping providers advance their education, and these can be key supports for advancing their compensation.

- Unprompted, many administrators shared that recent changes made to adult-child ratios and age requirements for child care providers were not beneficial and not utilized in their centers.

APPROACH TO THE SURVEY

Procedure

The ISU Data and Analysis Team (here forward referred to as “the team”) led the development of the focus group strategy, key questions, and facilitator guidelines with input from the Iowa Workforce Study Advisory Committee. Additionally, members of the team recruited participants and facilitated the focus groups.

To supplement learning from the Iowa Workforce Study provider survey, the team conducted focus groups with center-based program administrators followed by a short survey. The target sample was 50 administrators representing 50 programs. A total of 37 child care program administrators representing 37 programs participated. In February 2023, 8 focus groups and 3 individual interviews were conducted via Zoom, recorded, and transcribed for analysis. In the final minutes of each focus group, administrators were provided with a Qualtrics link to answer questions specific to the number of staff they had, minimum education requirements for various staff positions, and pay and benefits for each staff position. Participants and members of the team remained online during survey completion so members of the team could answer questions and provide technical assistance as needed.

Sampling

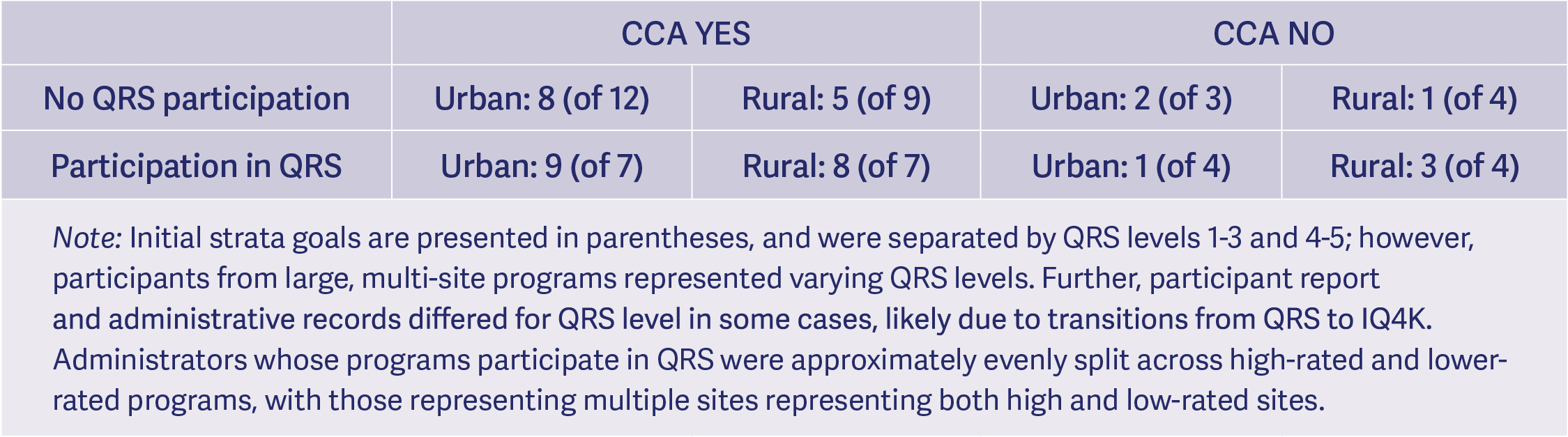

The team determined three criteria on which to stratify the sample of programs to invite to the focus groups–Acceptance of child care assistance (CCA) or not, rural or urban county, and QRIS participation and rating (does not participate, 1-3 stars, 4-5 stars)—resulting in 12 possible combinations (referred herein as strata). A list of active, licensed –center-based programs was retrieved from the Iowa Department of Human Services website on January 31, 2023. Proportion of providers fitting in each strata was determined and then used to inform sample selection from the full list. Note that every category was assigned a minimum of 2, thus, some strata are overrepresented, and others are slightly underrepresented. Programs were randomized within strata, and then identified for invitation based on the random order with additional consideration to program size. In other words, although program size (under 50 children, 50-100 children, more than 100 children) was not a formal strata, programs of varying sizes were invited prior to a multiple of a single size. Once programs were identified for an invitation, an email address for program administrators was retrieved through the CCRR public search website. Administrators were contacted and invited to participate via email. Early recruitment yielded a low response rate; thus, stratification of the sample was loosened such that strata informed who was sent invitations to participate, but any willing respondents were included. Initial strata goals and final participant characteristics are displayed in the table below.

TABLE 1. SAMPLE SIZE BY ORIGINAL RECRUITMENT COMBINATION

Analysis

Prioritized themes for coding were originally based on the provider survey data collected in Summer 2022 (see Appendix A) and the Fall 2022 focus groups (see Appendix B), and included financial compensation, benefits, and commitments to the field. However, given the unique nature of these interviews and the purpose to better understand how they recruit and retain their own staff, unique themes were required to best organize data from these administrator focus groups. The final coding scheme identified the following major themes: (1) Financial compensation & WAGE$ program; (2) other benefits (e.g., health insurance, retirement investments); (3) Recruitment, retention, & long-term commitment to the field; (4) Education, T.E.A.C.H., and succession planning; and (5) topics emerging from participants.

The following summary provides a description of each major theme, with relevant subthemes and exemplar quotes provided.

THEMES AND RESULTS

Higher Pay is Critical

Administrators recognize that increasing wages is crucial to being fully staffed and employing high-quality staff. They make decisions about starting rates and salary increases based on the position the employee is being hired for, education, and experience, and increase by an annual cost of living increase when possible. However, they know the wages for employees in their program are lower than other businesses and organizations across the education continuum. For example, many participants commented that their staff (who do not have two-year or four-year degrees) make less an hour than employees at local gas stations, grocery stores, and other retail stores. Participants who spoke of hiring employees with more education recognized that they were competing with the public school system, and simply could not offer the same pay.

Participants were also quick to discuss that increased staff pay could not be funded by the parents. In many cases, the point that teaching staff needed higher pay and families couldn’t pay any higher tuition was made in the same statement. Some participants shared that they had increased tuition to raise pay rates in the past year or two to help attract employees, and that they had hit the maximum amount that parents could or would pay.

In terms of salary supplement programs such as WAGE$ and recruitment and retention bonuses, administrators had mixed perspectives. WAGE$ was generally spoken of favorably, as a way to compensate more educated employees when the program could not increase hourly pay. Administrators found WAGE$

to be relatively easy for them to complete their part, and the smooth process made them more positive overall about WAGE$. One concern that was highlighted, often in conjunction with a conversation about the transition from QRS to IQ4K, was the link between WAGE$ and center QRS/IQ4K participation and rating. Participants expressed concern that the WAGE$ bonus an individual receives is tied to program-level efforts, decisions, and even equity barriers to achieving a high QRS/IQ4K level. Retention and recruitment bonuses received a more mixed response, with administrators citing inconsistency in the application process and time to receive bonuses as a challenge. Administrators highlighted that they did not use these bonuses as a recruitment tool because they would not be available to employees right away and because they (the administrators) feared changes to the program or funding that might make it unavailable at some point. Generally, administrators saw the recruitment and retention bonuses as a nice extra for employees who qualified but not necessarily part of their toolkit for recruiting and retaining high-quality staff.

Administrators Want to Pay More

“I’ll do anything to get my staff up to the wage that you know they deserve. When you talked about wages, of what we could do or what we would give, I would at least love to give every single one of my staff above what they make at McDonald’s and Target to start with.”

[administrator 101]

“[Other businesses say] I can’t find any workers, because my workers can’t find childcare. So somebody needs to step up to the plate and help these childcare centers provide childcare, and the only way we can provide it is to offer a living wage to our staff. It has always been very embarrassing to me that the vast majority of my staff, who are single parents, qualified for food stamps.”

[administrator 605]

“I would say our biggest issue is our starting pay for our area. We start out at $10, and then the teachers get $10.25 an hour to start, so that’s our biggest concern. I’m lucky right now that I just happen to have great group of people I work with, who show up every day, but when one does call and sick, or they need time off, it’s hard. I get pulled from room to room wherever I need to fill in.”

[administrator 704]

“I’d pay them what they deserve, and even more if I could. But I don’t. They’re mission-minded so they’re coming here for a reason. Then they want to work, and I get that. But it’s also nice to say your mission minded, but we’re gonna pay you what you deserve also. So, I couldn’t even, I can’t even give you an answer to say this is what I would like to pay them. I’d like to pay them with what’s comparable and what they deserve. But doesn’t happen right now”

[administrator 104]

“I do feel like we have to increase our hourly starting pay to compete with places that we lose staff to. Around here its Caseys. So a gas station will start off their employees at a higher rate than us. Also, fast foods as well, but then we do have some that we lose to some blue-collar jobs in this area. So, like factory assembly line work that starts off a lot higher that I don’t think we could ever compete with in the, you know, $20 to $25 range.”

[administrator 602]

“If they can go to any fast-food place, HyVee, any number of other places, and get paid significantly more per hour. Now the downside is, they may have to work nights, weekends, things like that, but it’s just when they have expensive rent, because the cost of everything has gone up, or just their grocery bill, whatever they’re gonna potentially take the higher paying job, even if it’s less desirable hours, because they need the money, so I can’t really compete with that. And that’s hard.”

[administrator 604]

“You know there’s a Subway that’s opening up by us, and it’s going to start at $14 an hour. And people can say what they want. ‘Oh, no, nights, no weekends.’ It does not matter if they can’t pay their bills. They’re going to go to the job that’s going to pay their bills and that’s just a fact, and I can’t fault them for that. I understand the very real reality of not being able to pay their bills so as much as I can try and sell it, and say no night, no weekends, no holidays. It’s, for me, I don’t even think it’s really a true factor for them. They have to be able to pay their bills.”

[administrator 601]

“We just basically start all of ours at a flat rate. We do 3 month performance raises, and then we do the cost of living yearly. And yes, it was very hard to get people in here. We went through turnover like mad, the first year that I was director. And yeah, you can go to Mcdonalds, and get paid almost twice what we pay for what we

do. So I get it all.”

[administrator 803]

Families Can’t Foot the Bill for Additional Pay

“To do our wage, this last wage increase that we did, we had to raise parent tuition, and pretty soon we’re gonna, I mean everybody, I’m preaching to the choir, but you know, we’re gonna price parents right out of out of child care, because nobody, I mean, it costs a college education almost to send your kids to daycare.”

[administrator 801]

“I think, I mean, like was mentioned before, it’s kind of hard now that these staff have had that extra income so then, all of a sudden not have it [if WAGE$ ended]. And so, I think, like with we mentioned before, our tuition would have to rise. And then you’re raising it too high for families, and then you’re losing families, and it’s just a vicious cycle to try to kind of balance all that, for sure.”

[administrator 804]

“But our church helps us. They support us financially and so that’s kind of how we get by. Otherwise, there’s no way that we would be able to stay open without our church help and funding.”

[administrator 703]

WAGE$ Program, Recruitment, and Retention Bonuses, & Other Salary Support

“I feel that we’ve hired some staff, knowing that they have that opportunity to get WAGE$. And if we were to lose that, I would say we definitely have to potentially increase our wages for those you know really, bottom line, bottom, tier staff. Otherwise. I mean, I think our program would still run, cause we did it without WAGE$ prior to. I think WAGE$ is just the bonus like a bonus to them. Here’s this, we recognize that you know you’re in childcare. And here, we’re gonna give you this bonus. So, I think that’s the way my staff really look at it. They greatly appreciate it.”

[administrator 101]

“Our problem with retention is that our twos and threes teacher, they’re like 10 cents an hour too much [for WAGE$] when you break their salary down, and then I think the biggest complaint is retention, like, like…for example, myself, I applied September 8 for retention bonus. I just received it 2 weeks ago. So, the processing time. It’s very frustrating that you like encourage employees to apply for these things, and then it takes 6 months.”

[administrator 603]

“In my dream world that child care facilities would also get a state per diem, like per child per day, like what the school districts get. So school districts get, you know, a little over $7,000 per child per year from the state. So, why not do something like that similar for the childcare child? Care is such a crisis and everything. Let’s instead of giving us money to build more centers that we can’t even staff, let’s [give] some money to the centers that are open and running and help them get staff, to retain staff, to keep positions open, so these families can get enrolled. I mean, I know there’s a ton of centers in this area that are still not operating at full capacity. So, I mean if we got, you know, just for, say, $3,000 per child, that we enroll, or that we have opening for I mean, that’s money that we can send back out to increase wages for staff that might entice them more to getting into the early childhood field. Because right now nobody’s going into it. So where are we gonna find staff”

[administrator 102]

“I think a benefit that did happen from Covid is that a light shown on child care obviously. And I see things changing, they’re trying to make that, and definitely we’re on the right track. We just need more. I think some of the programs that they’ve started are great. Like I said we, we have benefited from the WAGE$ program. But just continuing to help us as centers bridge that gap between affordable child care, and being able to pay staff what they deserve. So, yeah, I, I think we’re in the right direction. Hopefully. But just continuing.”

[administrator 804]

“it’s hard because they don’t work quite enough hours to get the WAGE$, and I think I could retain some of them. But we could just be open more. But the funding isn’t there for that, either.”

[administrator 402]

“Yeah, so I actually never used it [recruitment and retention bonus] as a recruitment piece because I just didn’t know how long it would be here. And so I just kind of chose not to use it in that sense. I didn’t want to promise somebody and then, like two weeks later, they said, “sorry, funding is gone and you don’t have it anymore.” So primarily what has happened is it’s been mostly retention for me. And then the few people that have come on board, it’s just kind of been a surprise, a nice perk for them.”

[administrator 504]

“And I said, ‘Hey, like this is such a positive. And I’m so glad we’re doing this. But, like the system is not working’, and I’m not the only director that feels like we’re turning a positive into a negative at this point because we’re getting these workers and we’re saying, you’re gonna get this bonus. But like 50% of my 25 staff that turned it in have got it, and the other ones have been waiting 5, 6, 7 months.”

[administrator 403]

“The WAGE$ check—your amount is tied to what your centers, IQ4K or QRS level is, and I am not a fan of that. I feel like if you are college educated and working in a low-paying field, that the amount of your checks should not be based upon what it is that your administration can pull off for a level because there are barriers to IQ4k and there are barriers to QRS including the trainings and things like that if you can’t afford for your staff to do them afterwards, because technically, if they’ve worked 40 hours, that legally should be overtime, that you’re paying them to do those trainings. So if you can’t do that, or afford to do that, then that can be a barrier for some centers that might not be able to get a higher IQ4k or QRS level rating so but there’s still college-educated staff working at a license center. So I would like to just see the you know, if you’re working at a license center in your college educated that you’re eligible for that.”

[administrator 403]

“Well, I thought it was a great thing. It’s been a great thing for my long-term staff. What I ran into was staff leaving immediately after they got that bonus, within 2 to 6 weeks.”

[administrator 401]

Variety of Ways Starting Pay is Determined or Employees Move Up the Pay Scale

“All of our pay rates are determined, based on the education. So, any raises based on the education. So, if they get bachelors, they’re raised, their pay would go up and then off.”

[administrator 101]

“So, we have a base rate, a pay, and then we look at education too, and age that they teach. Obviously, I have 3 sections of 4-year-olds and we participate in the statewide voluntary preschool program. So, not only do they have to have a 4-year degree, they have to have a degree in early childhood and a current Iowa license. So that would pay more than a teacher in my 2- or 3-year-old program,who may just have a 4 year degree with some early childhood background. So we have a base, and then we add on to that, depending on the requirements and education and that stuff.”

[administrator 103]

“So our position rates are based on basically the position in which they’re in. So right now, we’ve just recently switched over to, for our early learning centers, we’re only hiring full time. So everybody’s full time, and then for our school age programs, of course those are only part time, because we do before and after school. And then I mean we only have one kitchen person, everything else we outsource, cater in for food, and then we have one admin person, an associate director, and then myself. So it’s basically it’s based on the position. And then,

of course, years of service as they grow within. I have to say that we’ve got some staff that have been here for twenty-plus years.”

[administrator 102]

“So they get a 3% [annually]. Usually a 3% raise. We’ve done some different things because we realize our associate pay is pretty low. So, this year for the 2022 to 2023 school year, we did a like an incentive bonus thing. So when they sign their contract they got a $500 bonus, and then, if they stayed through the first half the year, they got another $250, and then in May they’ll get another $250, so like they got an extra $1,000, this year, because we can’t, I mean we’re trying to compete.”

[administrator 603]

“We don’t really have a pay scale here, you know, we start our part-timers out at a certain rate, and then our full timers out at a certain rate and then it just goes up from there. So, if you’re a lead teacher, you get a little bit more. If you’re a lead teacher with an associate degree, then you get, you know, this much. If you have experience, then I even add a little bit more into that that kind of thing. I will say that our starting pay for part timers is $11 an hour, and that’s actually pretty. It’s lower than most in the Des Moines area, but that’s what they’ve had to do to get the high school kids to come in and help, because like you can go flip burgers, for, you know, 13 or 14 bucks an hour and then so we don’t have any better?”

[administrator 802]

Benefits are Important, but Challenging to Provide

Administrators are aware that benefits are important, but they commonly have problems providing benefits because of the cost. A couple of program administrators indicated they were able to offer full-time employees robust benefits packages if the employees stayed with them for two or more years. In these exceptional cases, the program was tied to a larger organization where child care workers made up a small percentage of the employees receiving benefits. Administrators perceive that retirement funding and stronger supplement support for health insurance from the state government would be strategic both to recruit and retain people and get qualified people into the workforce.

Heterogeneity in the workforce and the needs of the workforce became apparent in conversations about benefits. Administrators generally talked about three populations—individuals under the age of 26 (including high schoolers) who tended to still access health insurance through their parents, individuals who were married and accessed health insurance through their spouse’s employment, and unmarried parents who primarily qualified for state-funded insurance. Administrators highlighted conversations with various employees about benefits. While some employees wanted access to benefits through employers, many prioritized having cash in hand. Where programs were offering health insurance benefits, in most cases it was only available to full-time employees, and employees also paid a portion.

Administrators had very little to say about retirement, recognizing that it was not within the scope of their program budgets to provide for retirement. One participant suggested access to IPERS or other state organized and supported retirement might help maintain retention in the field. Many directors felt their employees had to prioritize paying today’s bills over saving for tomorrow’s and guessed most of their employees did not have an outside retirement plan.

Free or discounted child care was an additional benefit discussed. Single parents were highlighted in these conversations on discounted child care. Some administrators expressed concern that these employees were receiving such a low wage that they were eligible for state insurance and benefits such as SNAP. For these workers, free or drastically reduced child care was a key reason for working in the program—if their child had free care while they were working, none of their pay went to child care. Other administrators specified recruiting (married or unmarried) moms of young children, including for part-time positions, because they could offer free or discounted child care when they couldn’t offer the other benefits. Most administrators see their employee’s needs for free or discounted child care for their own children and offer it as a key perk. However, they also recognize filling a spot with an employee’s child reduces the tuition coming into the center. Given the timing of the focus groups, some groups discussed the proposed plan for all child care employees to qualify for state child care assistance subsidy regardless of income. Administrators expressed favorable opinions about this idea, as it would mean the state investing more to cover their employees’ free or discounted childcare costs other than at the expense of the program’s income.

Insurance

“Some of ours are either on their spouses because they’re working somewhere else or don’t have it or are getting it on their own.”

[administrator 104]

“Our greatest competition is the University. At the beginning of the school year I was fully staffed. I’ve lost 4 staff to the university, and I can’t even come close to being able to compete with them. Their positions aren’t starting the wages aren’t starting much more than us, but they get university benefits. So I’ll never be able to compete with that.”

[administrator 601]

“That has been a deterrent for staff is that our insurance that we offer to them is a very high cost. So it’s there’s nothing else that can make up for that.”

[administrator 602]

“If you’re a lead teacher, you do get 50% of your single insurance premium paid. So kind of a goal is to up that and to up it for all of our full-time staff.”

[administrator 804]

“So we, we offer health insurance. We pay a $150 a month towards their health insurance. It’s health, vision, and dental, but because, as our agent says, they’re all women of childbearing age, it’s very costly, you know. Most of my employees, their insurance is like $270 to $280 a month. It’s based on their age. And so we pay $150 of that so they’re still paying, you know, most of them roughly $150 a month. The vast majority of my employees are still falling under their parents’ insurance, but they’re all right on that cusp, and they’re going to lose that soon. So, we always have the conversation of it, you know. Should you do our insurance? Are you gonna look at marketplace? Those kind of conversations. But most of them end up qualifying for, like, the Hawk-I program, or something like that through the State.”

[administrator 601]

“It’s a very robust benefit package that we do use as a recruitment and bargaining, marketing. But, you know, just say hey look at what you are getting. Those that choose not to take the health insurance…they’re on a spouse’s. We are hiring young adults, and so some of them are still on their parents’ insurance, or they say, “Oh, I’m young, I’m healthy. I don’t need it.” So they’re looking at the cost of health insurance, even though the agency pays for 80% and the employee pays for 20%, it still can be, you know, first time and young just realizing well, that’s what all these benefits cost up to that. They just choose not to enroll in benefits…it’s their choice, but those are the options in front of them.”

[administrator 201]

“Health insurance is a huge barrier. I mean every month when I talk to people about health insurance, I go around and count all the people in my building that don’t carry health insurance at all, because they, you know they choose not to, because they just can’t afford that. So, I would really like to see a health insurance benefit for them. I’ve never been a person that has felt like the government needs to step in and needs to solve all of our problems. But the system is broken, and parents cannot pay more.”

[administrator 601]

Retirement

“I don’t know exactly what the answer is, but I do agree that their probably needs to be some sort of government intervention, because, for example, we’re all licensed by the state. What if full-time people could get IPERS? I mean, maybe that’s something that should be looked into…I don’t know how that would work or what that would look like. But if people could have a viable retirement fund that would give them an incentive to stay in the field and stay in that job, that would be huge. And then, of course, health insurance is another huge thing…if we can recruit people that will work full time because they know they get IPERS, we would be a lot farther down the road in not only recruiting and retaining people, but getting good people that we want to keep you know that are really motivated to stay in the field and have a reason to, so I mean, I don’t know. That would be a pretty big commitment. But if we’re really saying that we’re investing in child care in the state of Iowa, to me that would be a really good way to do it.”

[administrator 604]

“The [organization] is fortunate that with us, having more than just child care that we are actually able to offer all of our full-time employees benefits, I mean, of course, it’s split between employer employee paid for, and then also all of our employees. This is one of our biggest perks is that they’re given 12% into retirement, full time employees do not have to put a dime into it. So that is a big perk that we have. Once they hit the qualifications of being employed for 2 years, they started getting 12% in the retirement”

[administrator 102]

“I looked into a 401K and I don’t know if anybody would, you know…taking that money, they need that money right now. And to put it into something, my employees don’t understand that that will come back to you eventually. But they want the money right now.”

[administrator 202]

“Well, we don’t offer any benefits. Again, we’re a nonprofit, and we’re through a church. Most of my staff is older and married, like their kids are middle school or high school, so they are with their husband’s insurance, you know. I think it would be nice if we had some way to do some, you know, even if we didn’t have the health care, [offer] retirement because, I think, like just even empowerment. To have your own retirement separate from your husbands is important”

[administrator 603]

Free/Reduced Child Care

“I think that’s kind of like a double-edged sword because most parents that work in child care, they’re being paid a non-livable wage. So if they just applied for state [subsidy] anyways, they’d probably get it so like, you know, does it sound really great? And [are] there gonna be some people that maybe are married and are just over the threshold, or something, and could get it? Yes, absolutely. But we all know that the majority of the workforce right now is girls that are 26, and under that maybe are a single mom, because they just want to be with their baby. And you know they’re probably making $13 an hour, and they’re going to, you know, receive state child care subsidy anyways, if they applied.”

[administrator 403]

“We have kind of a mix of staff here. Most of them are, I would say, over 35, and most of them have been with me for several years, so we’d have very little turnover. But I really attribute a lot of that to the school that we’re affiliated with, because we have some moms that work here and get discounts off their school. So that helps a lot.”

[administrator 802]

“The thing is, like, for a while to keep staff we had to give staff kids free childcare which is not helping our bottom line.”

[administrator 705]

“So, one of the things that I’m very interested in I’ve just heard rumblings about this, so I don’t know what exactly it means. But the potential that full-time employees can be categorically approved for CCA for their children. And what does that mean? I don’t know, but I’ve certainly lost plenty of staff who have said to me, I’m having a baby and by the time that I have to pay for my baby to go to the day care center, I’m making 50 bucks a week I might as well stay home, and so, if categorically approved for CCA means that their children are going to be free and it’s not gonna cost them anything to bring their children to child care, we may have more young mothers re-entering the workforce. I’ve also lost families who have said, I can’t afford not to work, but I can’t afford to work this job that I love, because by the time I pay the child care… So again, I think categorically free, depending on what that means, may be a huge benefit for us.”

[administrator 605]

“But I just want to chime into that because I that’s how I keep a lot of my staff is because it is free daycare. You know. So when they come, you know, and they have one or 2 kids, and they don’t have to pay daycare when they’re with me.”

[administrator 402]

Recruitment, Retention, and Sustaining the Workforce

Among the many challenges that administrators in the field face, recruitment, and retention are the greatest. While there is high demand for additional childcare, and administrators have the physical space to receive children, staff shortages obligate administrators to limit the number of children they receive. Administrators also indicated that often they need to take on additional roles such as janitorial work and classroom teaching support to account for labor they cannot hire.

Staff shortages and recruitment problems have been accelerated by the COVID-19 pandemic. For example, recruiting hourly staff to work in the afternoon hours, such as high school students, has become very difficult. Part of this challenge is associated with the taxing nature of the job in contrast with the low hourly pay and lack of benefits. In fact, administrators are aware that the low pay and few benefits provided may be driving workers out of the field to either (1) less taxing jobs, such as gas stations or supermarket positions, or (2) school district positions, where more salary and best benefits can be obtained.

While administrators are aware that low-wages are a problem for retaining staff and that their workers may deserve more pay, they have difficulties providing their staff with a competitive wage without asking for more money tuition from parents. Some administrators currently rely on stabilization funds or grants for this. However, these are not consistent or secured every time. Overall, administrators suggested that retaining staff and balancing income is a difficult balancing act.

Despite the difficulties of the field, administrators stated that there are very committed workers. Some staff remain deeply committed to the field even through the difficulties that the COVID-19 pandemic presented, as they know their work is meaningful for children and families.

Impact of Staff Shortage

Limiting Enrollment

“So we have here, if we’re fully staffed, about 25 staff right now, I have about 20 to 22 less full time than I need. Two classrooms closed. We kind of survived through the whole covid thing until the end of last summer, when we had a couple of people move out of town, couple of our long-term leaders who had to take jobs with benefits and higher pay, and we have raised our pay over the last two years, but we haven’t been able to fill those gaps.

[administrator 401]

“And I’m in Davenport, and we have a waiting list of over 400 children who are looking for care, and I have 1, 2, 3, 4, 4, 5 of my classrooms that are not full because I don’t have staff to be in ratio”

[administrator 102]

Moderator: “Gotcha. So your license capacity in terms of based on space would allow you to have more children. But you don’t have enough adults to supervise those children.”

[administrator 102]

“Correct, and we won’t just hire anybody. So, we’re still very picky on who we bring in, because we want quality care for our kids. But and you know, then, on the other aspect, it’s if we can’t fill our spots. I mean my school age programs. There’s not one school age program that’s operating at capacity, because I don’t have the staff. I mean, there are days that we get really close to having to close after school programming because our staff call off or are out sick or need a vacation day, or have something going on at their college that they need to be at or whatever it may be. So that’s, I mean that’s where we’re sitting right now is, I mean, if we were fully staffed we would have well over, you know, we’d have close to a thousand children in our programs. And we’re offering a little bit about 500 between before and after school and our 2 early learning centers right now.”

[administrator 102]

“So our center is not at full staffing. We have capacity for 107 kids and obviously 10 teachers is not enough to cover that because we accept children from 6 weeks to 12 years of age. So, just with ratios, it’s not enough, and we have been struggling with a shortage and staff or a shortage in people willing to apply or finding people since covid, actually. So, let’s see, I would say, our biggest barriers are low pay and a lack of benefits.”

[administrator 702]

Administrators in the Classroom and Other Duties

“Currently I’m doing the janitorial because, you know, [city] is a small community and we have 2 cleaning services or businesses in the town but they don’t have any employees. No one is working for them, so we can’t go through them. And you know, it feels like a vicious cycle, you know. I could get more kids if I had people that would work.”

[administrator 701]

“I think, within the last year, as a director, I’ve probably spent more time in the classroom than I have like in years combined…I end up in a classroom some days, you know, maybe just some days, just to help with breaks, or maybe some days, you know, we had three teachers that had the flu or something, and I’m in a classroom for a whole day. I go home. And I’m like, okay, well, not only my like, mentally tired, but I like. I’m also physically tired.”

[administrator 403]

“So this is my church. I’ve always known about this children’s center, and I happened to be on the Church Council when the previous director terminated her employment, in October of 2020, and that’s when I stepped in because I thought they’d find a director in a few weeks. I think the thing that I like you, [other participants], have ended up in the classroom too much, which means things don’t get done on this end like they should.”

[administrator 401]

Recruitment: Challenges Finding Staff

Most Challenging to Find Certain Types of Workers

“The problem that I’ve had with my staffing is in, is after the 3 o’clock hours, and it’s because of I never had any problem getting high school workers, especially cause we’re affiliated with like [high school] here in [city], and not very far at all a couple of minute drive. But the pandemic hit, and I can’t hire a high school staff to save my soul.”

[administrator 802]

“So I have a large staff, but yeah, it’s still I don’t know not what I would consider to be full. My biggest gap at the moment is like afternoon staff, like everybody knows that we’re open 6:30 to 6. No one has any interest in staying till 6 o’clock, and so that’s a challenge for us, and the staff that I do have. So that’s mostly high school students, so 16 and older that help us get our building to the end of the day. And then they do all the like cleaning and shutting down at the building, and all of that good stuff. As far as like full-time teachers, I think I finally gotten to full staff.”

[administrator 705]

“So, I don’t know if it’s just an area thing, but I’m hearing people say that they’re starting teachers at $10 and $12 and what not. But we’re in small town, Iowa, and just based off of, our staff are paid through child tuition, and if we were to raise child tuition anymore than we already have it at, I don’t believe we’d have a lot of interest, or a lot of continuing care. So our starting rate for those without education or experience in the field, it does land more around $8 an hour. Obviously, we have staff members paid more than that. And currently our biggest draw for staff is that our center is offering free childcare for those staff members while they’re working. And yes, it does come. It hits the center hard, but we don’t, we haven’t found another way to cope with that, or to draw people in otherwise, because we don’t have health insurance, we don’t have retirement insurance or retirement benefits.”

[administrator 702]

Schedule Can be an Advantage and a Barrier

“But I do feel like in order for us to be competitive, even though we offer holidays off, some of our holidays are paid, but we offer no weekends. The latest you can work is 6’clock at night. I do feel like we have to increase our hourly starting pay to compete with places that we lose staff to around.”

[administrator 602]

“Well on the other part of no nights, no weekends, no holidays, is if you’re a college student and you’re an athlete on top of it. The hours that I need you to work may not work for you. And so you’re probably going to have to work nights and weekends if you’re going to have a job because we’re a college town, too. And we used to get a lot of college students, and we don’t anymore. I mean, we really, really struggle for staff. I could easily take another 65 children, maybe more. Combined my school age programs, but I can’t find staff.”

[administrator 605]

Nature of the Work is Challenging

“So you know, we filled a lot of these positions, and I’ve never had the experience like we’re having this year. They’re here for, you know I had one that, you know, lasted half a day, and then we broke for lunch, and they never came back. So again, it’s just, I think, what everybody is hearing and experiencing now is just, you know, that worker shortage, you know, sadly. You know we pay higher than the fast foods and other places, but sometimes, when you look at the you know just the energy and desire it takes to work in early childhood, sometimes working at a fast food or a Casey’s or someplace else, you know, even though it may be paying, you know about a dollar or two less than what we offer them…that is more suitable to what they’re like, what they want to do and deal with. Because challenging behaviors and mental health has certainly been an issue this year in classrooms.”

[administrator 201]

Retention

“I’ve got a lot of teachers who are on low-income housing, so they can only have like 28 hours a week. They can’t go any more than that, and that works for me. I can fill in those extra, the wonky hours. I’ve got a couple of high schoolers that do 3:30 to 5:30 Monday through Friday for the extra stuff, kids that volunteer because then later on they’ll be 16 and able to jump in there but [took] 5 years at one center to finally get smooth.”

[administrator 607]

Long-Termers

“Nobody’s working here to get rich. They love kids and believe in our mission and those kind of things, too. So, we’re talking about a little bit of different type of employee than someone who’s looking at Target and just wants to, you know, punch in, punch out and then be done.”

[administrator 103]

Education, Training, and Succession Planning

Administrators spoke of education as a key determinant of pay and increasing education as a primary method to increase pay. Administrators represented centers with a wide range of minimum education expectations: from those who employed current high school students to those who employed multiple degrees and licensed teachers. There were, however, administrators who expressed that education (e.g., “fancy degrees”) was not as important to them as experience and being a good fit for the center.

The T.E.A.C.H. program helped many providers, mostly adults older than traditional college age, further their education. Administrators saw benefits to the program in helping recruit people who wanted further their education and retain employees during their schooling and the required commitment period after. Administrators mentioned a desire to pay employees in lower positions more for the important work they do but felt limited (within their own budget and with access to programs like WAGE$) for employees with only a high school diploma. Repeatedly, administrators acknowledged the benefit of T.E.A.C.H. requiring a time commitment beyond completion of the program. Administrators also saw the benefits the T.E.A.C.H. program brought to their programs. For instance, T.E.A.C.H. employees have implemented what they have learned from their classes into their own classrooms to boost quality improvement. Additionally, as employees earn additional education credits and credentials, centers are able to move up in quality rating systems or acquire accreditations. Administrators also praised T.E.A.C.H. for making a positive impact on most of its users’ individual lives, such as helping them get their diplomas and teaching license, and in turn, helping them progress in their careers to leadership positions and higher salaries. T.E.A.C.H. participants who advanced their education qualified for increasing WAGE$ supplement rates. A few administrators did express challenges with needing to cap the number of employees they had participating in T.E.A.C.H. at a given time, and that occasionally, when someone in the T.E.A.C.H. program completed a program leading to licensure, they would then leave child care settings for public schools.

Administrators were asked about succession planning in an attempt to better understand how they are planning for future leadership. A few programs had a structured process in place, while others had no plan.

Education is a Key Determinant of Pay

“All of our pay rates are determined based on the education. So, any raise is based on the education. So, if they get bachelors, they’re raised, their pay would go up.”

[administrator 101]

“We just changed our salary wage scale for our program…We start at a base rate of $13 an hour, and then we tell them as soon as you’ve completed CPR/first aid, mandatory reporter, and Essentials, you go to $13.25. When you finish pathways and safe foods, $13.50. When you’ve done the ERS scale related to your assigned age group and then you go to $13.75, and if you’ve completed all of the trainings that I just listed plus PBIS or in a school age program, school age, social skills and school age matters are at $14. If you have a CDA, you automatically start at $14.50, and then our onsite supervisors automatically start at $15.”

[administrator 605]

“So we have a base rate of pay, and then we look at education too, and age that they teach.”

[administrator 103]

“All of our lead teachers are licensed teachers in the state of Iowa. So obviously our 4-year-old teacher has a higher salary, because that’s part of the statewide free preschool program.”

[administrator 603]

T.E.A.C.H Program

“We have. Yes, I have worked with gals who have went all through the T.E.A.C.H. program, got their endorsement, things like that. We do have multiple girls here on the WAGE$ program as well with Iowa AEYC, too. So, our college educated gals do receive those checks based upon our IQ4K level every 6 months, and that is a huge benefit … when your girls do get those CDAs and stuff, they will get those WAGE$ checks. Then every 6 months as a bonus. Yep, depending on where they’re in is so right now we have girls that get a $3,000 check every 6 months from WAGE$.”

[administrator 403]

“And then I also have staff that have done T.E.A.C.H. as well…two lead teachers in our 3-yearold room, got her diploma through that program, and then I have the gal that teaches our voluntary preschool that’s contracted through the state. She got her teaching license. She did her whole education through that so, and both of those gals have been with me since they were like 16. But not with me necessarily, but been here since they were 16. So, it’s a good program.”

[administrator 801]

“So, I do participate in the T.E.A.C.H. I actually did teach myself 14 years ago, when I started it. The benefits are, they get that release time. Their education is paid for, and most of it. It is also an incentive when we do interviews. You know, letting them know that we have this T.E.A.C.H. program; after 6 months we’d love to put you back to school. Get what you need for an education…And it is the big, big benefit to us is, we know we can’t pay those lower end positions like the ones that only have the high school diploma. We can’t pay them what they deserve to be paid, so that is one of the benefits that we recruit with, when we are doing interviews and continuing as they are with us after 6 months we also do use that for recruitment WAGE$.”

[administrator 401]

“We’ve utilized both programs here. And I do like about T.E.A.C.H. that there’s also some requirements, as far as staff sticking around if you participate, and so we’re able to, you know, retain those staff, and there’s some raises. And there’s different options you can pick as far as the T.E.A.C.H. program. But we’ve definitely seen benefit from that. They’re able to come back and share some things they’re learning, and some of their classes and implement that into the classroom, which is a great thing.”

[administrator 101]

Succession Plans and Leadership Building

“Okay, I would say that’s part of our onboarding when we do get staff, I’ve been with our program for 14 years. And I started as a teacher associate, and I’m now the director. So, I definitely share that with the staff and give them like, you know, there’s opportunity for growth in this program. This is what, you know, I went through as for the actual succession planning, we had procedures for every position of everything that they do, even down to my position, so that we can, you know if somebody happens to be gone or something happens we have procedures of all the little detailed items that they do. So we use that for the succession planning.”

[administrator 101]

“No, again. We don’t have people knocking down the door, and so to come work. No. There’s none really, so like, if I would leave, then you know our board and our executive director would need to find someone else to fill that role.”

[administrator 104]

“And we’re in the same boat. There’s no formal process either that our preschool board, and then our church personnel committee would be responsible for filling my position-the executive, or the assistant director’s position. So there’s no formal plan in place.”

[administrator 103]

“So my program does not have a succession plan. It’s something that my, as a nonprofit, my board has talked about. But we haven’t, we haven’t done anything…Not that I’m all that and a bag of chips, but it would, if I left tomorrow, it would be hard pressed to continue. And I’m not planning on going anywhere. I have like 13 or 14 years before I can retire, so we’ll get it at least that far, and then we’ll see what happens.”

[administrator 801]

“So, I am relatively new to the director role. I would say I took over in March of last year, so kind of how it worked for us as I was in the assistant director. There are 2 of us at my center, and we both applied for the job. We both kind of said that we were interested. If we hadn’t been they would have, I’m sure, reached out internally to other people, but we both happen to be interested in the position. We both interviewed, and so that’s kind of how I landed in my job. So, if I were to leave, I would say the same thing sort of would happen. I’m trying to promote from within and, see, I know some of our teachers who have been here 15 to 20 years and don’t wanna leave the classrooms, but I know some of them do so. I would assume some of them are interested in seeing how the management office side of it all works, because it’s kind of eye opening.”

[administrator 805]

“We again are fortunate with the University to get a lot of interns, and actually one of our directors, one of our assistant directors, and our current, we call our office assistant, started as interns with us, and so that’s definitely helped our administrative roles, I would say, if it weren’t for that it would be hard, I think we’ve learned over the years that sometimes the best teachers, just it’s just a different role to be an admin role than it is in the classroom.”

[administrator 804]

“I know here in the [organization] we tend to open it, these kind of positions, up to everybody outside and inside, and then they narrowed down who they wanna you know, who best fits. You know what they need. And then everybody has to interview. It’s not just a given that you’re gonna go from assistant to director, but at least, if she didn’t get the job she would know enough about the job to be able to help transition that person in should she decide to stay. If she didn’t get the job so…But it’s never been a secret what I do, and I invite people to say, ‘Hey, spend a day with me. You’re more than welcome to see what I do’, and you know. So we just try to transition people, you know, and get everybody to know what everybody does, because it just helps for better understanding and better communication overall in that.”

[administrator 802]

Unsolicited “Other”

Administrators routinely rely on a variety of care providers in order to staff their settings, such as stay-at-home moms, college students, and high school students. While this requires administrators to accommodate their needs and schedules, it also increases their available workforce. Notably, this workforce variety is reflected in how benefits are provided to workers. Specifically, there seems to be three typologies in which workers fit into. Some workers who are single mothers may require health insurance to be provided by the childcare setting or governmental supports; married workers may rely on their spouses to access benefits; and younger students access benefits through their parents.

Administrators criticized the recent changes in the regulations about teacher-student ratios. According to the newly approved regulatory, child care centers are allowed to have one caregiver oversee up to 7 two-year olds and one caregiver can oversee up to 10 three-year-olds. The administrators expressed frustration with the new regulations as they may put even higher demands on the already burn out teachers while not solving the problems of compensation and retention. In fact, most of the administrators mentioned they choose not to follow these new ratios because they are both unsafe for children and too demanding on the teachers.

Heterogeneity Among Workforce

“I’m fortunate right now to have stay-at-home moms who just kind of want a side job, you know. So then when the kids kind of graduate out, then I’m searching every year, I’m searching for new staff. So, it is a problem. But I’ve kind of reached out to that outlet which has been really helpful for us, because a lot of these moms are professionals, you know. One has a doctorate. All the other ones have a 4-year degree. So, it’s been really helpful for me.”

[administrator 402]

“So, we’re able to recruit quite a few colleges students that are education majors, early childhood majors. It’s a perk. The downside is their schedules are challenging because they’re in class all at this same time.”

[administrator 604]

“I know I have other employees who, based on their rate of pay, or what they earn per year, they do qualify for state health insurance, and then others who are married, who have spouses, insurance that they’re held under. And then our one high school student obviously would still qualify under her parents, plan. So that’s how we’re doing it. Currently.”

[administrator 702]

Changes to Teacher-Child Ratios and Group Sizes

“It was frustrating not too long ago, when a few of the changes that were made to help child care programs was to increase ratios and lower the age of people that can be unsupervised with children or be supervising children, and I thought that is not solving anything, and I have not adopted those ratios because I think it’s not appropriate. And so we still go 8 to one with threes instead of 10 to one, and I and I don’t hire anyone with less than at least a high school diploma.”

[administrator 604]

“I just sometime get frustrated with the ratio or the ratios that we have. I, since they bumped them, I just feel like it’s not feasible and you’re stretching staff thin, and then staff get frustrated and they need to tap out or take a break, because we have all these behavior kids and it’s just, it’s a lot. And then they don’t wanna stay in the child care for us. They wanna leave and go find a better-paying job and something else that they could do and not go home stressed and not being able to give their time and energy into their families at the end of the day, because they’re at the end of their rope so that’s just something I would say.”

[administrator 703]

“I just wanted to say that it was a good point that the new ratios, or it seems like that the child care initiatives that have come through recently are all just focused on boosting the amount of children in the center. When, if you’re invested in creating more spots for more children and creating more quality, early childhood places, centers or home care, or whatever that’s not necessarily the answer. That maybe the direction should be focused on assisting staff and that realm of things, rather than just focusing on how many more can we put in here, or how many more can we provide for? It’s answering or solving one problem, while not solving the actual root of the problem.”

[administrator 702]

“Don’t burn out your teachers over more kids.”

[administrator 705]

“So, I’ll add a little to that. The changing of the ratio, that didn’t help me at all, either. I can only have so many kids for the size of room that I have, which is what everybody else can have too. So, if my room can only hold 20, say, 12 kids changing the ratio for a 3-year-old to 10 does not allow me to take 20 kids. It allows me to leave that one teacher with 10 kids, which, who wants 10 3-year-olds. Can the state representatives come, spend a day, and a 3-year-old classroom with 10 of them, and tell me how that’s… All it did was frustrate my staff, because now they can… Now, especially at the beginning and the end of the day, they are by themselves with 7 to 10 kids for those two age groups where before I had to pull in somebody else. And most days because of our staffing, my 3-year-olds are running at 1 to 9, which is legal. I don’t like doing it. I wouldn’t want to be in the 3-year-old room with 9, 3year-olds… but yeah, so that just that didn’t help us at all.”

[administrator 801]

“I know they just changed the ratios for threes and fours, and we as a school, decided not to increase the ratios as we just can’t imagine ten 3-year-olds with one teacher. So, we’re remaining with the 8:1 ratio. Then, we even do even less with our 4s as well, we do tend to do 10 with that. But we could do 12:1, I guess. That seems pretty scary.”

[administrator 502]